Wildlife Conservation Magazine – September/October

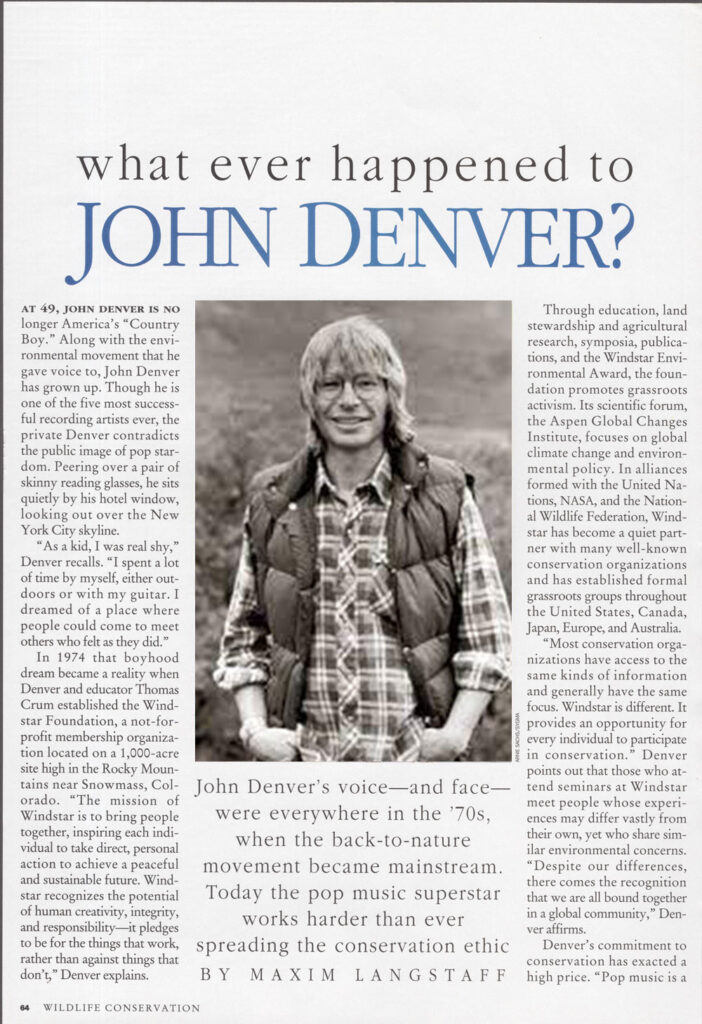

John Denver’s voice–and face–were everywhere in the ’70s, when the back-to-nature movement became mainstream. Today, the pop music superstar works harder than ever, spreading the conservation ethic.

At 49, John Denver is no longer America’s “Country Boy.” Along with the environmental movement that he gave his voice to, John Denver has grown up. Though he is one of the five most successful recording artists ever, the private Denver contradicts the public image of pop stardom. Peering over a pair of skinny reading glasses, he sits quietly in his hotel window, looking out over the New York City skyline.

“As a kid, I was real shy,” Denver recalls. “I spent a lot of time by myself, either outdoors or with my guitar. I dreamed of a place where people could come and meet others who felt as they did.”

In 1974, that boyhood dream became a reality when Denver and educator Thomas Crum established the Windstar Foundation, a not-for-profit membership organization located on a 1,000-acre site high in the Rocky Mountains near Snowmass, Colorado. “The mission of Windstar is to bring people together, inspiring each individual to take direct, personal action to achieve a peaceful and sustainable future. Windstar recognizes the potential of human creativity, integrity, and responsibility–it pledges to be for the things that work, rather than against things that don’t,” Denver explains.

Through education, land stewardship and agricultural research, symposia, publications, and the Windstar Environmental Award, the foundation promotes grassroots activism. Its scientific forum, the Aspen Global Changes Institute, focuses on global climate change and environmental policy. In alliances formed with the United Nations, NASA, and the National Wildlife Federation, Windstar has become a quiet partner with many well-known conservation organizations and has established formal grassroots groups throughout the United States, Canada, Japan, Europe, and Australia.

“most conservation organizations have access to the same kinds of information and generally have the same focus. Windstar is different. It provides an opportunity for every individual to participate in conservation.” Denver points out that those who attend seminars at Windstar meet people whose experiences may differ vastly from their own, yet who share similar environmental concerns. “Despite our differences, there comes the recognition that we are all bound together in a global community,” Denver affirms.

Denver’s commitment to conservation has exacted a high price. “Pop music is a big, big business, and the primary motivation is profit,” he admits ruefully. “After I became the biggest-selling pop artist in the ’70s my record company wanted me to continue doing the same thing. But if there’s no artistic growth taking place, soon you get trapped in an expression of something that is no longer you. Look what happened to Elvis–[the process] killed him. It’s very, very frustrating. For me, the costs have been enormous.”

Denver, who was named Poet Laureate of Colorado in 1975, says he’s done his best music in the last ten years. His singing and writing today have a resonance not found in his mega-hits of the mid-’70s. But lacking much in the way of record company promotional support, albums that reflect his environmental interest– Seasons of the Heart, One World, and It’s About Time— have reached a smaller audience. in sell-out world wide concert tours, the demand for Denver’s ’70s classic Rocky Mountain High continues to eclipse that for his newer, less familiar songs such as African Sunrise and Amazon.

“In Amazon, my hope was that people listening to it would repeat the words, hearing themselves saying ‘Le this be a voice of no regret’,” says Denver. he continues, “The Buddhists say, ‘As air to the bird, as water to the fish, so is resentment and regret to humankind.'”

These days you’re not likely to hear John Denver singing in Hollywood anthems such as We Are The World. Instead, you’ll find him touring East Africa on behalf of UNICEF, performing benefit concerts for wildlife in Alaska, or speaking to groups of corporate executives on strategies for a sustainable future. “It is strange to me how resistant and fearful people are of change,” he reflects. “We need to be willing to look anew at the principles and values we hold dear. If America is going to serve in a leadership role, we must make some tough ecological choices that will carry us into the twenty-first century with integrity and a promise of continuing life. That requires going inside ourselves. If each of us acts from a position of authenticity, we will find the courage to make the tough choices that are necessary.”

Denver observes that modern man feels separated from the rest of life on Earth. “Our Judeo-Christian upbringing has taught us that we have been given dominion over the Earth. Yet it is the diversity of life that desperately needs to be sustained, but we are not mindful of that diversity.”

Recently Denver went on a fact-finding trip to East Africa on behalf of the World Hunger Project, a group that raises money and sends food where needed. He sounds impatient as he describes the conditions. “We must help people, particularly those living in the developing world, to understand that they are honored and respected for living a sustainable life that is not based on profit but on the ability to work together as a community.” On a visit to China, he was amazed by the magnitude of change. “MTV is showing up in a country of a billion people. Everybody wants electric lights, everybody wants a TV, everybody wants what they see on the magic box. But with its huge population, China can’t support that kind of development. The impact of this on their natural resources will be devastating.

By popularizing the conservation ethic over the years, the singer-songwriter has helped numerous conservation groups such as the World Wildlife Fund, the Sierra Club, and Friends of the Earth to achieve the public recognition so crucial to the success of their missions. “All of the things I’ve gotten involved with are connected with the environment, whether it’s renewable energy resources, hunger, or wildlife conservation. Within the coming ten years we will have to ensure that Earth’s ecological systems remain viable to support biodiversity for future generations. In this decade we will make the choices that determine whether this planet will remain habitable for humans and most species.

The signature optimism that has won so many hearts for Denver remains intact. “We have to believe that our actions matter. You don’t have to do everything. Do the things you can do–teach your children, express your views.”

Honored with two presidential awards in recognition of his humanitarian efforts in the cause of ending world hunger, Denver is also widely respected for his tireless work on behalf of conservation. For him, celebrity is a responsibility. “I’m a singer and songwriter and I’ve had the opportunity to be a voice for certain things,” he says. “For me, those things have to do with the environment–are the nature that I feel a part of, not separate from them.”

Maxim Langstaff is a writer for NYZA/The Wildlife Conservation Society